Serving Rural Africa

What does healthcare look like for people who live outside of cities?

That’s a question worth wondering about.

So often African healthcare challenges are framed as big problems, dark clouds of death and despair hanging above us. Things to fix.

From the Navajo Nation to the Turkana region in Kenya, people live outside of cities. This makes it harder and more expensive to get healthcare and other services to them. That is a reality, not something that needs fixing. It is a reality we can design for.

It would be cruel to ignore the big problems– 82% of the extreme poor in Africa live in rural areas. But we can reframe these problems as design challenges that lead us to insights that might be applied on a global scale. Innovators in places like Zambia and Kenya are already building models to deliver 15 cent rehydration salts to remote villages and to connect a doctor to the worried mother of a feverish infant over the phone in her home far away.

I’m working with a great team at the African Healthcare Funders Forum to build a course that reframes how we think about African Healthcare, and how we fund it.

Our first healthcare session was focused on serving rural Africa. So often, this conversation centers around community health workers and telemedicine. My team asked participants to reframe four current mental models in relation to how we think about serving rural Africa: expand the definition of healthcare investing beyond facilities, invest in how people move around the health system, support asynchronous and non-smartphone based telemedicine models, and embrace blended finance. Here is a tour through why we believe these reframes are essential in creating a caring and effective rural healthcare system.

80% of healthcare is not driven by what happens in the “health environment.”

Our zip code, our income, whether we teach, drive a cab, or sit at a computer - these are things that make up our health. If we eat chips from a bag while walking to the bus or sit down for dinner, these behaviors affect our health.

Social, economic, environmental and behavioral factors all have a much bigger impact on how healthy we are than the time we spend in a clinic does. But healthcare investing has been traditionally focused on clinical care, which only influences about 20% of an individual's health (1). This reality is especially relevant in rural areas, where the traditional health environment is harder to access.

In Uasin Gishu county, people gather in the village community center to discuss their farming investments. Everyone makes a contribution to the group savings account, and individual members discuss and vote on group investments or approve individual member loans. In the back of the room, a traveling pharmacist is setting up a blood pressure cuff, rapid diagnostic tests and medicines on a table.

Dr. Sonak Pastakia and his team at AMPATH know that “20% health solutions” are not enough. They set up a network of savings and loan groups where people got together and talked about the things they actually cared about: how are we going to make money and feed our families?

Credit: Dr. Sonak Pastakia, Purdue University

A small healthcare investment in getting these groups up and running yielded large gains in health. The BIGPIC model for linking healthcare to group savings and loans delivered significantly better outcomes (measured by lower blood pressure) than patients who only used clinics for care. It is also a fully self-sustaining model. Because patients earn income through these microfinance groups, they are able to pay for the attached healthcare services.

Yet they are having trouble raising capital to scale. Funders want to break their model up into recognizable boxes: invest in the distribution of diabetes medication, but not the setup of the savings and loans groups where medication is distributed. We need new mental models on what it means to be a healthcare investor.

Some concentration of services is necessary.

You probably don’t want to get your hip replacement done by a surgeon who has only done one that year. Specialized people and equipment benefit from volume. Healthcare systems should not only invest in the equipment, people and facilities that people need– they should invest in how people move around between those things.

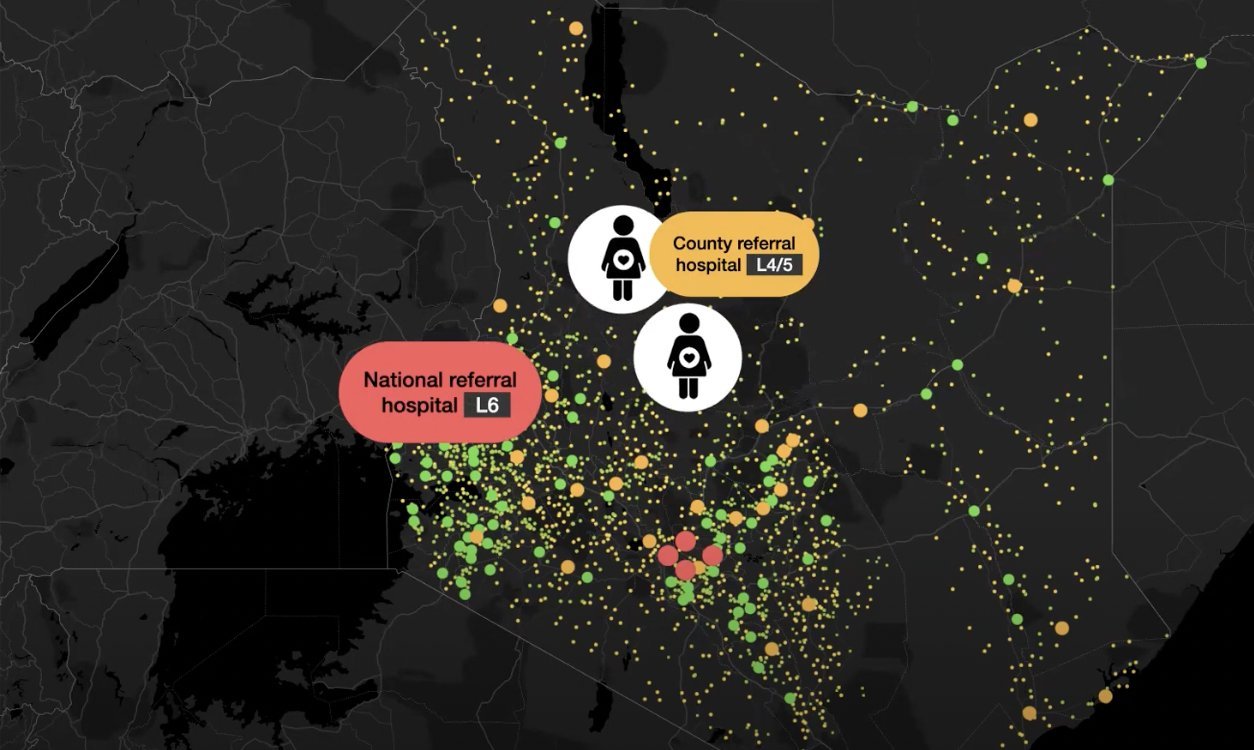

Rescue by Flare is a startup building a platform for patient logistics. By mapping facilities, specialists and equipment, Flare helps patients get where they need to go on the first try. This means women in rural areas aren’t taking a two hour bus or cab ride to a hospital while in labor only to find that it closed early due to power cuts.

Credit: Rescue by Flare

In cities, Flare started their business focused on how fast they could get an ambulance to people who called for one. But in rural Kenya, they expanded their mandate to smart escalation and patient logistics. Healthcare funders often focus on adding resources to underserved areas. There is nothing wrong with that– but smart platforms to make better and more accessible use of the resources we have are an important piece of the rural healthcare puzzle.

You don’t need fast internet for effective telemedicine.

We’ve been using communication systems to discuss care for patients ever since the fax machine. So why are we still talking about telemedicine like it is a shiny new digital health toy?

Dr. Pratap Kumar has been building digital health tools that work in rural Kenya for the past decade. His telemedicine platform does two things differently than most out there.

First, it allows clinicians to connect asynchronously to work on a patient case. This is important because most patient care does not need to happen **in this second.** Tools that allow a reproductive health specialist to talk to a nurse about a patient’s care save that patient a lot of time and effort traveling. Asynchronous telemedicine also supports healthcare providers by enabling them to work in teams. This is valuable in rural settings where nurses do not get to spend as much time with specialists, who often live in further away towns and cities.

Second, his telemedicine application integrates with custom tools to capture data from paper records using simple camera phones. Not every clinic needs a laptop or internet connection to provide and share information.

Credit: Health-E-Net PaperEMR Platform

Blended Finance is essential for serving rural Africa.

All of these case studies leveraged a mix of financial instruments across the spectrum, from investments to grants, to have impact outside of urban centers. Maria Rabinovich, Co-Founder of Flare, spoke about how their VC backed healthcare platform partnered with philanthropic capital providers to break into Western Kenya. Dr. Pratap Kumar has investable technology, but uses grants to expand into Turkana in Northern Kenya. Still, some funders do not like to participate in “blended deals.” We believe that to reach rural populations, where the healthcare need is the highest, solid business models and their investors must learn to work with social impact bonds, research grants, impact debt and other forms of concessionary capital.

Oftentimes, working rural means working with local governments, and these partnerships are time intensive and difficult. Funders can help with more than capital by getting good at things that are hard for startups, like lobbying, rule-making and negotiating with governments.

We see potential in rural healthcare. Funders looking to invest in rural healthcare should embrace that healthcare does not start and end at the clinic, could fund patient movement and not just infrastructure, could imagine telemedicine beyond smartphones and get ready to work with different types of funders. Comprehensive, kind healthcare systems that use data, build resilience and put health at the center are the future of serving rural Africa.

(1): https://pophealthmetrics.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12963-015-0044-2

Photo by Abubakar Balogun on Unsplash